A community that converts cars to electric. Part 2: Damien Maguire interview

Damien is an electrical engineer also known as the BMW EV conversion person. He has been converting cars to electric for over 10 years.

This is part two of a series of interviews:

- Kevin Sharpe from New Electric Ireland. Running courses to convert cars to electric.

- Damien Maguire. An Electric Engineer that converts cars to electric.

- Part 3: Johannes Huebner on how he wants to democratise electric car conversions.

Damien, tell us how did you start converting cars to electric?

It would be nice to say it all started with a single spark, like watching “Who killed the electric car” but in reality it was many things at the same time.

I have always been interested in cars, and they have started to become a bit samey. Around 2007–2008 time I started looking at car conversions to electric in anger, the stumbling block was always high costs. It was hard to get into, particularly in Europe. Everything needed to come from the USA. I priced all the parts and it came to somewhere between €15000 and €20000. That amount was for parts excluding batteries. The project used a basic DC motor, forklift controller, a very basic setup by today’s standards. It was completely off putting.

Around 2009 I came across [Paul Holmes], in the US Instructables youtube he was developing an open source DC motor controller. I am an electronics engineer by profession. I specialised in power electronics, so I was able to get involved with it. I ordered his kit for about €150 and bought a forklift motor for a few hundred euros and before I knew it I had a car that moved without engine power!

I thought I would convert one or two cars maybe, but there were more parts, components, ideas and ways of doing things becoming available. Then there was these “Lithium batteries” they promised things that seem impossible in the Lead acid era.

My first electric car project went 12.5 miles with lead acid batteries, the batteries weighed 600kg. I changed that to a lithium battery pack in 2012 or 2013. The new battery pack weighed 140kg and the car went 40miles.

I got another car, a BMW 5 Series that houses a 38kwh lithium battery that can go 110 miles and can drive on the motorway, and go wherever I wanted to go with it.

It has been quite a journey and I’m happy to be doing this full time for the last 3 years .

Reading online about car conversions, there were a lot of concerns raised about weight distribution, torque, etc. Can you tell us about that?

One of the biggest problems when learning about car conversions is misinformation. A typical myth is about how Lithium batteries will burn down your house and car, which is not true if used properly.

People have been customising cars for the last 150 years. Any kind of custom car build will put weight, components, stresses and mechanical differences into what is a mass manufactured vehicle. This is why it’s so important to have car people involved in making conversions, so you don’t make mistakes that are easily avoidable.

For me the main driver is to be able to use modern OEM parts in car conversions. This is the next big leap that will enable us to get away from the idea that conversions need to cost €100,000 and they don’t.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am designing an open source control system for the Tesla model 3 drive units. This work is interesting and “cool”. However, the most important thing I am working on at the moment is being able to reuse the Toyota and Lexus hybrid parts. These parts are more readily available, much more affordable and also (I will be roasted by the Tesla community of course by saying this) they are much more robust than their Tesla counterparts. They don’t have the horsepower figures that Tesla parts do, but at the end of the day that is not necessarily what people need or want. What I am trying to do is to make it so that these components can be used outside of their parent vehicle. It is about developing the hardware and the most importantly, the software solutions that enable us to use these parts in cars that were not designed for them.

When you mention the open source parts do you mean, the boards, the chip or everything combined?

It’s everything, all those elements, generally combined. Interestingly, for the Model 3 batteries, I am also excited to be using FPGAs for the first time.

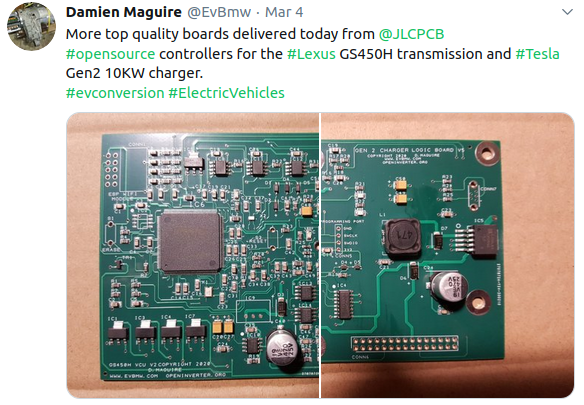

On this side of things, a big enabler that we discovered in the last six months is a Chinese company called JLCPCB where I can print a handful of circuit boards for very little money, meaning that we can try things and progressively improve them.

How do you design the boards?

There are many different packages you can use. I use Design spark PCB. These are multilayered boards, which are good for signal integrity, noise isolation and unity. Fortunately this is a process that JCBPLC supports.

What is your relationship with open source?

It can be very hard to open source something, you put a lot of work into it and it can be discouraging to get negative comments… at the same time it is encouraging to know that people are using what you worked on and even better when they contribute back. I especially appreciate that on the software side, since I am not very good at it. Johannes Hübner is a huge part of this, he designed the [Open Inverter System](https://openinverter.org/, I think if he wasn’t doing what he’s doing I probably wouldn’t be doing what I am doing. I mean, there are lots of really good people out there too, but Johannes is a key enabler for me.

How did you come across Johannes Hübner?

Around 2014 I got my first AC motor inverter and it was all closed source, after looking at this from a pure reliability point of view I thought, I am not putting this in my car! Too much that can go wrong! So I started looking around for alternatives, and found this website selling a kit, an open source AC motor controller and it was really simple, to the point I thought that it couldn’t be real, but I bought a kit for about €60 and when it arrived, I built the thing and got the motor turning! We kept in touch from there on. In some ways this is how Open Inverter started.

How does one convert a car?

Well, how long is a piece of string?

When doing a conversion, you are trying to place a component that was never meant to be there, so, of course, nothing fits. You will weld, cut, create bracketry, line stuff up, you need to be able to use a milling machine etc. The good news is that the custom car community are very familiar with these processes, they have been putting things that weren’t meant to be there for a long time.

Talking to custom car people is a good place to start if you want to do a conversion. Most of them are very interested, because they like doing things that haven’t been done before. They get a car because it’s something that defines them, they want to put their own individuality into it. For example, I got a BMW 8 series that has a Tesla Model S drive unit, the only reason I could do that is because I know a very talented custom car person called Dave Gormley, he had to engineer a complete rear subframe for this car.

So, anyway, the main steps for converting a car, at a high level are:

Drive train work. Talk to custom car people or get on working if this is you.

Engine conversion : post about your project on the Open inverter forum projects section for integration.

Battery: easier now, depends on your budget and availability.

Vehicle integration: The good news here is that most modern cars started using a lot of electrically driven accessories that would traditionally be engine driven, for example: power steering , brake vacuum system, air conditioning, all these are 12 volt driving. Driving instruments and all that, varies from simple analog systems all the way to CAN, so when you are converting a car you need to go through each system and solve the problems as they arrive.

Last words

A place to start is to be in the Open Inverter forum, we try to keep the level of misinformation there to a minimum. Go there, read the forum and do something! Don’t forget, the most important tool is that bit between your two ears!

Thanks so much to Damien Maguire for his time and doing this interview for Coders4Climate.

If you liked this article, you might like the previous article in the series: Kevin Sharpe from New Electric Ireland. Running courses to convert cars to electric.